With Russian forces bearing down on Kyiv, the orders to Maksym Skubenko and the opposite males in his volunteer militia unit on Tuesday had been easy: Put together. Heeding the instructions, the unit spent a lot of the day digging up soil, then packing it into luggage. “So if somebody shoots at us, the bullets will hit the baggage,” Skubenko explains. He and his fellow in a single day troopers know very nicely how helpful these defenses is perhaps. They’ve already had a number of armed standoffs. The unit cleaned and checked their weapons and moved on to mixing the liquid for Molotov cocktails, following directions on a poster handed out by the authorities, filling a number of hundred glass bottles.

In his downtime, Skubenko checked his work messages. The 30-year-old is CEO of the most important unbiased outfit monitoring disinformation in Ukraine, VoxCheck, which provides analysis to corporations like Fb. As Skubenko shifts from combating the Russians on-line to preventing them face-to-face, VoxCheck has continued to churn out studies chronicling false data disseminated by the Russians: about Ukrainian shelling, mass breakouts from Ukrainian jails and residential invasions by the Ukrainian Nationwide Guard, amongst many different (unfaithful) matters.

“I didn’t anticipate to be right here,” he stated Tuesday night, sitting on a bench exterior the constructing serving as his group’s barracks. “I didn’t anticipate my nation to go to battle.”

Since Russia’s assault on Ukraine started lower than per week in the past, all the nation has rapidly shifted to battle mode. Greater than 600,000 folks have fled. The 2 largest cities—the capital Kyiv and Kharkiv to the east—have come underneath assault. About 80% of the 190,000 Russian troops amassed on Ukrainian borders have entered the nation, assembly spirited resistance that has unexpectedly slowed the better-equipped Russians. A part of the protection includes volunteers like Skubenko. Practically 40,000 answered the federal government’s name to arms, echoing one made eight years in the past throughout a battle with pro-Russian separatists.

“I didn’t anticipate to be right here,” Skubenko stated Tuesday night, sitting on a bench exterior the constructing serving as his group’s barracks. “I didn’t anticipate my nation to go to battle.”

In comparison with the opposite recruits, Skubenko has a singular perspective on their adversaries. He has spent years attempting to foil Russia’s ongoing digital marketing campaign in opposition to Ukraine. VoxCheck was based in 2014 by Tymofiy Mylovanov, an economist and College of Pittsburgh professor, following one other second of tumult: a civilian-led revolution that pressured President Viktor Yanukovych out of workplace and sparking a reform mindset in Ukraine. Then, as now, Ukraine’s media panorama stays skewed by Russia, with customers inclined to Putin’s propaganda pushed by means of newspapers, tv and, in fact, the web, largely by means of social networks maintained by Russian state-affiliated shops like Sputnik and RT. (Meta, Twitter, YouTube and others earlier this week both banned or restricted these publications.) There appeared to be a spot—and a necessity—for an unbiased fact-check outlet to name out deceptive data from Russia and, at instances, the Ukrainian authorities, too.

“There was sturdy demand for an goal credible evaluation of what’s taking place in Ukraine, particularly when it comes to economics, as a result of for a few years, economics as a science was nonetheless very backward in Ukraine,” says Yuriy Gorodnichenko, a Berkeley economics professor who aided VoxCheck’s creation. On the identical time, conventional media sources lacked the belief of their viewers. “There was lots of credibility hole in Ukraine,” says Gorodnichenko, presently the top of VoxCheck’s supervisory board. “You could have the Soviet previous—folks at all times fearful that anyone’s an agent, anyone’s being paid to say that.”

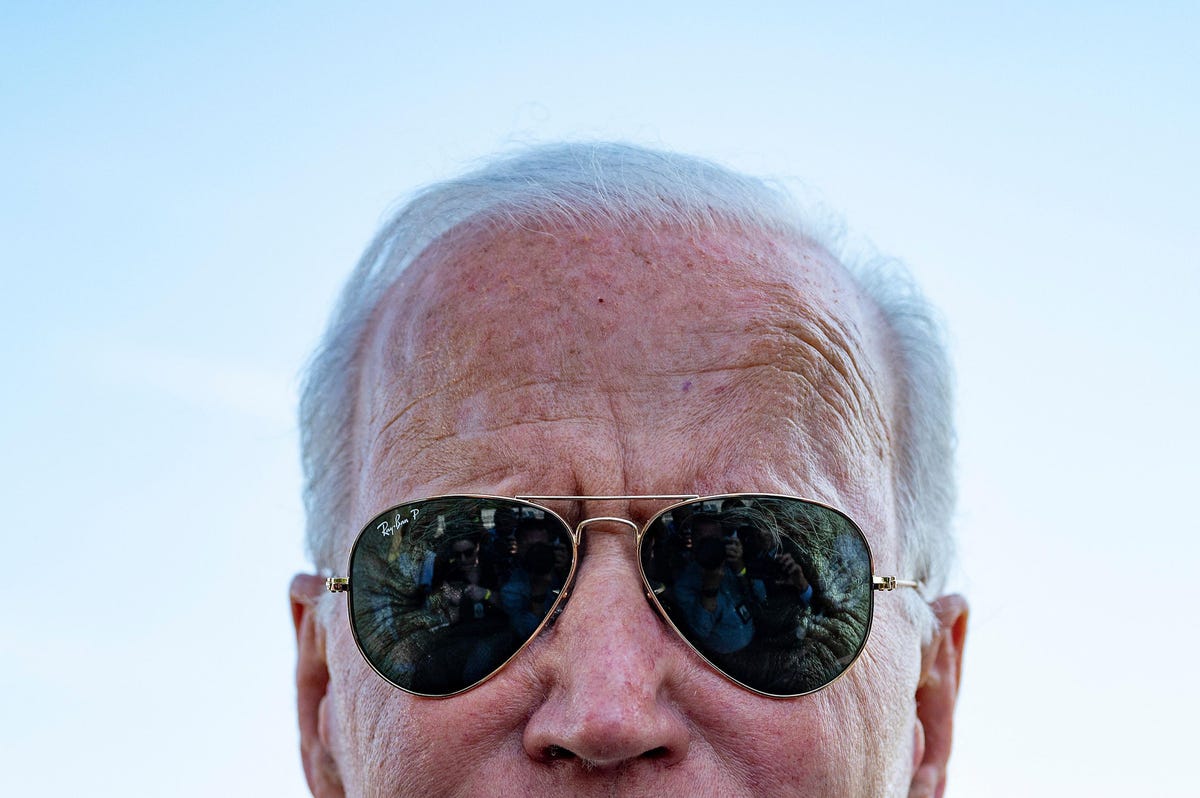

Maksym Skubenko stands on obligation Wednesday whereas a fellow volunteer solidier takes his photograph.

Courtesy of Maksym Skubenko

Inside a couple of years, VoxCheck’s profile had risen. It issued studies a couple of Russian troll manufacturing facility on Twitter, the well being of Ukrainian banks and a quantitative index measuring the truthfulness of the nation’s least truthful politicians. The group has turn out to be a key companion to corporations like Fb, which depends on its evaluation to guage content material posted from Ukraine. It has additionally accomplished fact-check work for UA:First, a TV information channel, and for Forbes Ukraine, an unbiased, licensed version of Forbes. VoxCheck can be a well-liked useful resource for Ukraine’s governing elite. VoxCheck’s founder, Mylovanov, switched from reporting in regards to the latter group to being a member of it in 2019, turning into Ukraine’s Minister of Economics. He turned VoxCheck over to its chief economist, Ilona Sologoub, who handed the CEO function to Skubenko on December 1. The positioning receives about one million visits every month, a determine small by American requirements however sizable for Ukraine.

Skubenko had been with the group virtually for the reason that begin, becoming a member of in 2015. “He grew up with VoxCheck,” says Gorodnichenko. Raised in a small city 140 miles from Kyiv, Skubenko obtained an economics diploma from the Lviv Banking Institute and for a short while labored as an auditor on the Nationwide Financial institution of Ukraine. A few weeks in the past, Skubenko was engrossed within the work of monitoring Russia throughout conventional and digital media. He and different VoxCheck researchers had picked up a brand new story line that baselessly recommended an imagined power disaster in Iraq would imperil Ukraine. It tried “to revive a story that we’d die with out Russian gasoline,” he says. They traced 5 Telegram channels to suspected ties to Russian particular forces and labored to catalog pro-Russian sentiment extra casually distributed by rich Ukrainians and politicians.

On Thursday, Skubenko’s world ceaselessly shifted. He had tried two days earlier to register for the volunteers however had been turned away and instructed they’d name him later. He returned to a recruiting submit in Kyiv on Thursday, however they’d no weapon for him. He went to a second, the place he did lastly be a part of up. The primary evening, Skubenko, his hair tightly cropped and a big, spade-shaped beard enveloping his face, and his battalion mates slept on wooden pallets padded with flattened cardboard bins. The following day, some folks gave them sleeping luggage.

Earlier than the previous week, Skubenko had solely fired a gun throughout a couple of days of coaching as a youngster. At that second station, he obtained some ammunition and a semi-automatic rifle, although he doesn’t know the precise make or mannequin. “I believe it’s Ukrainian,” he shrugs. He does know the gun makes use of 7.62-millimeter bullets, the bigger of the 2 commonplace rounds for an AK-47. Skubenko hopes the larger measurement helps “after we’re capturing at vehicles with Russian forces,” as he places it.

Skubenko and his squad have already skirmished, he says—fights he suspects concerned pro-Russian Ukranians who had been in Kyiv earlier than the battle began. In a single, a dark-colored Jeep sped to a cease exterior their submit to return to fireside on police pursuing them. “They had been capturing the police. Then they began capturing us. Then we began capturing them,” Skubenko recollects. He moved a number of individuals who had turned up on the station to volunteer to security and joined his comrades for the firefight. They killed certainly one of their attackers. Three extra surrendered to the police, he says.

A number of the dozens of Molotov cocktails that Maksym Skubenko and the opposite volunteer forces readied this week.

Courtesy of Maksym Skubenko

Skubenko’s unit operates in lengthy shifts, and not one of the males has gotten greater than three hours of relaxation in current days. (He remembers the exception fondly. “There was in the future after I acquired seven hours of sleep,” he says. “That was the greatest day.”) He has saved up by means of social media, primarily WhatsApp and Fb, along with his household and associates. His grandfather has holed up in his rural residence, and whereas he could also be alone, Skubenko causes that the previous man will not be completely defenseless. “He has a machine gun someplace in the home,” he says. His father has entered the volunteers, too, and Skubenko hopes his father could also be in Kyiv quickly. His mom is volunteering at a hospital whereas monitoring her son’s updates on Fb. In a submit to his Fb web page, she addresses him as “my coronary heart” and writes, “As a mom, I am crying, wailing. As a Ukrainian girl, I help you and settle for the selection you’ve got made.” She ends with a now frequent rallying cry: “Glory to Ukraine!”

When Skubenko might talk along with his VoxCheck workforce on Tuesday, the dialog revolved partly across the workforce’s video technique. He checked in along with his contacts at Fb and the standing of a number of different partnership contracts. Most pressing had been the calls to Poland, the place he’s attempting to arrange new financial institution accounts for VoxCheck. “If one thing occurs to the banking system in Ukraine, our group can not keep with out cash,” he says.

His consideration sparkles from business considerations to one thing extra critical. “Sorry, I have to go,” he says. An early warning in opposition to potential intruders has gone out. “I’ve to go.”

Because it seems: false alarm. He returned to his barracks, and he and the opposite beginner troops loved a heat meal, a dinner despatched over by a pizza restaurant improbably nonetheless working, their rifles prepared and the Molotov cocktails secured close by.

MORE FROM FORBES

MORE FROM FORBESRichest Ukrainians With Billions To Lose Close Ranks As Putin Unleashes WarBy Giacomo Tognini

MORE FROM FORBESNo Longer A Billionaire: Russian Banker Loses More Than $5 Billion Amid Putin’s WarBy Iain Martin

MORE FROM FORBESBiden And Allies Are Coming For Russian Billionaires’ Yachts: Forbes Tracked Down 32. Here’s Where To Find ThemBy Giacomo Tognini